Conservative groups are working to undermine support for Montana’s Medicaid expansion in hopes the state will abandon the program. The rollback would be the first in the decade since the Affordable Care Act began allowing states to cover more people with low incomes.

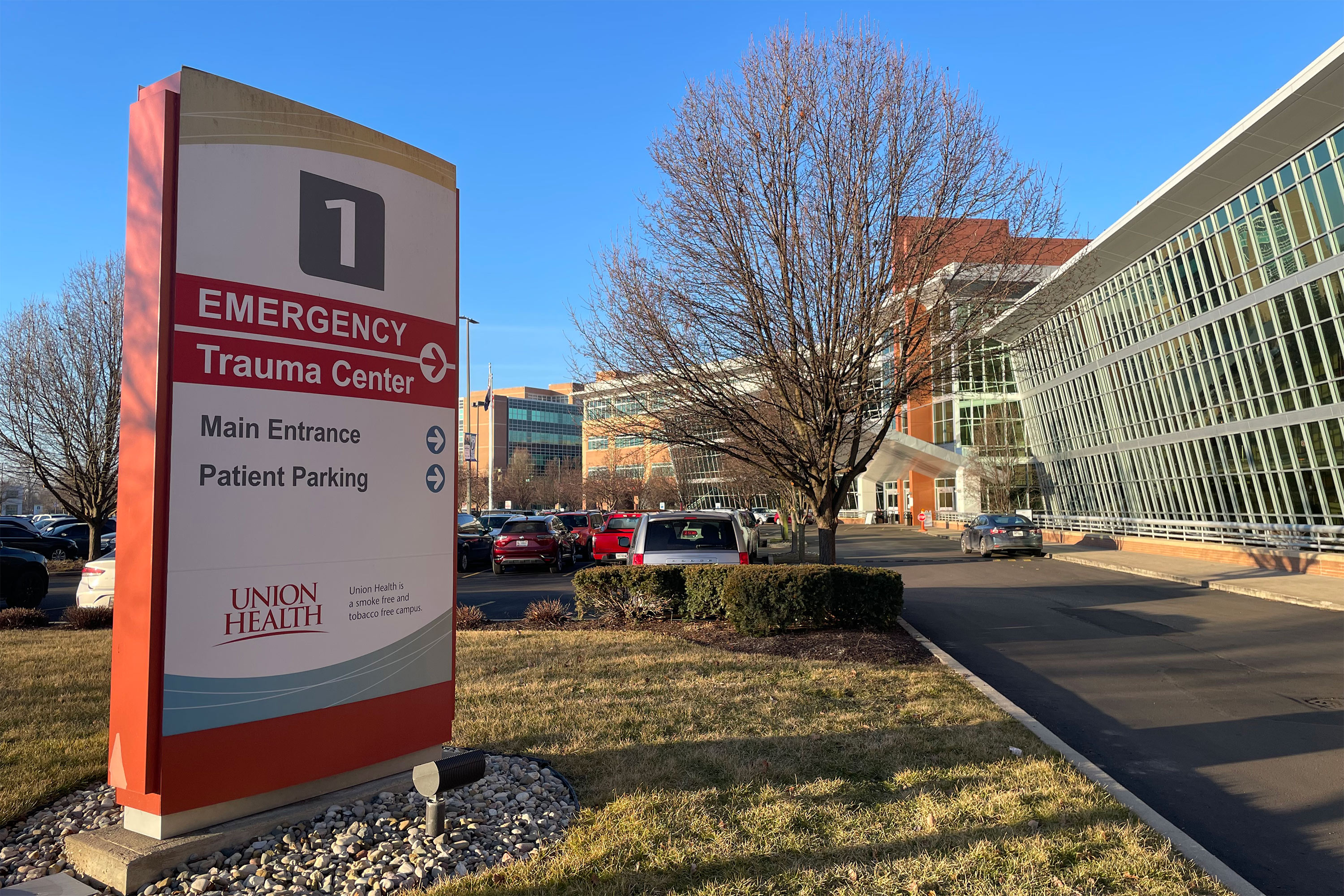

Montana’s expansion, which insures roughly 78,800 people, is set to expire next year unless the legislature and governor opt to renew it. Opponents see a rare opportunity to eliminate Medicaid expansion in one of the 40 states that have approved it.

The Foundation for Government Accountability and Paragon Health Institute, think tanks funded by conservative groups, told Montana lawmakers in September that the program’s enrollment and costs are bloated and that the overloaded system harms access to care for the most vulnerable.

Manatt, a consulting firm that has studied Montana’s Medicaid program for years, then presented legislators with the opposite take, stating that more people have access to critical treatment because of Medicaid expansion. Those who support the program say the conservative groups’ arguments are flawed.

State Rep. Bob Keenan, a Republican who chairs the Health and Human Services Interim Budget Committee, which heard the dueling arguments, said the decision to kill or continue Medicaid expansion “comes down to who believes what.”

Email Sign-Up

Subscribe to KFF Health News' free Morning Briefing.

The expansion program extends Medicaid coverage to adults with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level, or nearly $21,000 a year for a single person. Before, the program was largely reserved for children, people with disabilities, and pregnant women. The federal government covers 90% of the expansion cost while states pick up the rest.

National Medicaid researchers have said Montana is the only state considering shelving its expansion in 2025. Others could follow.

New Hampshire legislators in 2023 extended the state’s expansion for seven years and this year blocked legislation to make it permanent. Utah has provisions to scale back or end its Medicaid expansion program if federal contributions drop.

FGA and Paragon have long argued against Medicaid expansion. Tax records show their funders include some large organizations pushing conservative agendas. That includes the 85 Fund, which is backed by Leonard Leo, a conservative activist best known for his efforts to fill the courts with conservative judges.

The president of Paragon Health Institute is Brian Blase, who served as a special assistant to former President Donald Trump and is a visiting fellow at FGA, which quotes him as praising the organization for its “conservative policy wins” across states. He was also announced in 2019 as a visiting fellow at the Heritage Foundation, which was behind the Project 2025 presidential blueprint, which proposes restricting Medicaid eligibility and benefits.

Paragon spokesperson Anthony Wojtkowiak said its work isn’t directed by any political party or donor. He said Paragon is a nonpartisan nonprofit and responds to policymakers interested in learning more about its analyses.

“In the instance of Montana, Paragon does not have a role in the debate around Medicaid expansion, other than the testimony,” he said.

FGA declined an interview request. As early as last year, the organization began calling on Montana lawmakers to reject reauthorizing the program. It also released a video this year of Montana Republican Rep. Jane Gillette saying the state should allow its expansion to expire.

Gillette requested the FGA and Paragon presentations to state lawmakers, according to Keenan. He said Democratic lawmakers responded by requesting the Manatt presentation.

Manatt’s research was contracted by the Montana Healthcare Foundation, whose mission is to improve the health of Montanans. Its latest report also received support from the state’s hospital association.

The Montana Healthcare Foundation is a funder of KFF Health News, an independent national newsroom that is part of the health information nonprofit KFF.

Bryce Ward, a Montana health economist who studies Medicaid expansion, said some of the antiexpansion arguments don’t add up.

For example, Hayden Dublois, FGA’s data and analytics director, told Montana lawmakers that in 2022 72% of able-bodied adults on Montana’s Medicaid program weren’t working. If that data refers to adults without disabilities, that would come to 97,000 jobless Medicaid enrollees, Ward said. He said that’s just shy of the state’s total population who reported no income at the time, most of whom didn’t qualify for Medicaid.

“It’s simply not plausible,” Ward said.

A Manatt report, citing federal survey data, showed 66% of Montana adults on Medicaid have jobs and an additional 11% attend school.

FGA didn’t respond to a request for its data, which Dublois said in the committee hearing came through a state records request.

Jon Ebelt, a spokesperson for the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, also declined to comment. As of late October, a KFF Health News records request for the data the state provided FGA was pending.

In his presentation before Montana lawmakers, Blase said the most vulnerable people on Medicaid are worse off due to expansion as resources pool toward new enrollees.

“Some people got more medical care; some people got less medical care,” Blase said.

Reports released by the state show its standard monthly reimbursement per Medicaid enrollee remained relatively flat for seniors and adults who are blind or have disabilities.

Drew Gonshorowski, a researcher with Paragon, cited data from a federal Medicaid commission that shows that, overall, states spend more on adults who qualified through the expansion programs than they do on others on Medicaid. That data also shows states spend more on seniors and people with disabilities than on the broader adult population insured by Medicaid, which is also true in Montana.

Nationally, states with expansions spend more money on people enrolled in Medicaid across eligibility groups compared with nonexpansion states, according to a KFF report.

Zoe Barnard, a senior adviser for Manatt who worked for Montana’s health department for nearly 10 years, said not only has the state’s uninsured rate dropped by 30% since it expanded Medicaid, but also some specialty services have grown as more people access care.

FGA has long lobbied nonexpansion states, including Texas, Kansas, and Mississippi, to leave Medicaid expansion alone. In February, an FGA representative testified in support of an Idaho bill that included an expansion repeal trigger if the state couldn’t meet a set of rules, including instituting work requirements and capping enrollment. The bill failed.

Paragon produced an analysis titled “Resisting the Wave of Medicaid Expansion,” and Blase testified to Texas lawmakers this year on the value of continuing to keep expansion out of the Lone Star State.

On the federal level, Paragon recently proposed a Medicaid overhaul plan to phase out the federal 90% matching rate for expansion enrollees, among other changes to cut spending. The left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has countered that such ideas would leave more people without care.

In Montana, Republicans are defending a supermajority they didn’t have when a bipartisan group passed the expansion in 2015 and renewed it in 2019. Also unlike before, there’s now a Republican in the governor’s office. Gov. Greg Gianforte is up for reelection and has said the safety net is important but shouldn’t get too big.

Keenan, the Republican lawmaker, predicted the expansion debate won’t be clear-cut when legislators convene in January.

“Medicaid expansion is not a yes or no. It’s going to be a negotiated decision,” he said.

![Healthy High Protein Oatmeal Chocolate Chip Breakfast Bars [gluten-free + no added sugar]](https://i0.wp.com/healthyhelperkaila.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/OatmealChocolateChipBarsFeatured.png?fit=1536%2C1521&ssl=1)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·