Marilyn Vargas, who supports a household of six, gathers food donations at a pop-up food pantry held outside the Easthampton Community Center in Easthampton, Massachusetts. Karen Brown/NEPM hide caption

toggle caption

Karen Brown/NEPM

Hunger in America looks very different from the stereotype of malnourished children trying to survive a famine in a low-income country far away.

In the U.S., hunger is often much less obvious, but it's there — in the disruptive behavior of a third-grader who missed breakfast or the chronic anxiety of parents carefully rationing out boxes of cheap macaroni for their children.

You can also see hunger in long lines at a pop-up food pantry at a community center in Easthampton, Massachusetts.

That's where Marilyn Vargas found herself in November, pushing a grocery cart past a table of free food just after the season's first snowstorm. She threw in large packs of chicken breasts, some cookies, a giant box of Cheerios, rice, beans — all for her household of six.

The family's sole income comes from her federal disability check, Vargas said, supplemented by government programs like SNAP, and food donations. When the Trump administration delayed November's benefits during the government shutdown, "I was very worried," Vargas said.

She couldn't stop thinking about a difficult time a few years ago when they lived in North Carolina, far from any food bank. When her transportation fell through, she couldn't get to her retail job, 20 miles away. There was no paycheck and therefore no money for groceries.

"I felt terrible — I was crying. I was desperate," she recalled. "The only food I had, I gave it to my kids."

The pop-up food bank sets up twice a week outside a community center in Easthampton. Karen Brown/NEPM hide caption

toggle caption

Karen Brown/NEPM

Eventually, Vargas' sister learned about the crisis and helped her move the family to western Massachusetts, where food programs are easier to access.

But Vargas remains anxious about food, and she doesn't expect politicians to look out for her.

"I don't think they've ever been hungry," she said. "Especially Trump. He's never been hungry because his father was rich."

Hunger's effects show up in behavior and brain development

In 2023, 13% of American households were considered "food insecure" by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

There's no more recent public data, because the Trump administration canceled the annual survey, calling it "subjective, liberal fodder."

But in fact, food insecurity takes many forms in the U.S., and its relative invisibility contributes to policies that make it worse, according to doctors, public health experts and people like Vargas. They say politicians have failed to grasp that going without food, even for short periods, can take a significant physical and psychological toll.

"They think, 'Oh, there couldn't possibly be hunger in America,'" said Mariana Chilton, a public health professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Many people assume all hungry children "have distended bellies and flies in their eyes," she said.

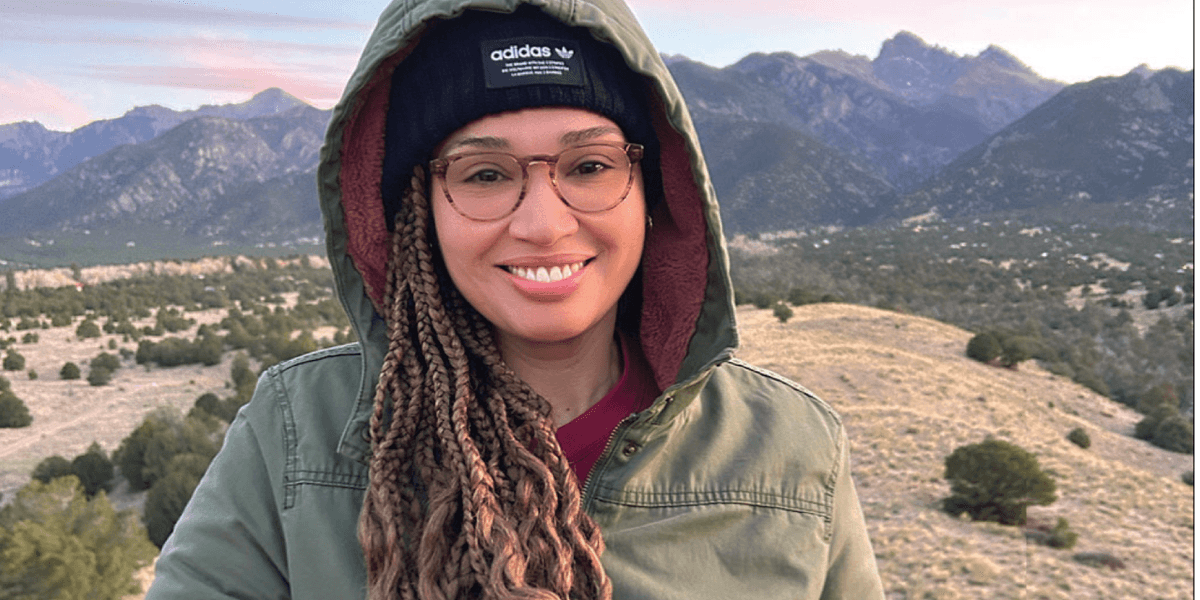

Mariana Chilton researches food insecurity and trauma as a professor of public health at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Karen Brown/NEPM

hide caption

toggle caption

Karen Brown/NEPM

In reality, Chilton said, hunger can manifest as teenagers too tired to participate in after-school sports or elementary-age students who arrive to class agitated.

"They can't focus. They may be more likely to get in fights with their peers or not be able to listen," she said.

Even a few days of hunger can affect brain development, especially among babies and toddlers who need fuel to make critical connections between brain cells.

"They are growing 700 neurons a second. So any interruption in good nutrition is going to affect the way that they interact with their world," Chilton said.

"Their body starts to slow down, to try to conserve energy. Even just one or two days of reduced intake is going to affect their cognitive, social and emotional development."

Many people assume that children can overcome early trauma, including hunger or malnutrition, said Dr. Diana Cutts, chair of pediatrics at the University of Minnesota Medical Center and an investigator with Children's HealthWatch.

"There is a collection of myths that fall under the heading of 'What doesn't kill us makes us stronger' or that 'Children are resilient,'" Cutts said.

"But science tells us that trauma and adversity do not usually make anyone — kids or adults — stronger or better," she explained. "It far more often does the opposite, causing injury associated with lifelong increased risk for poor health and shorter lifespans."

The long tail of poor nutrition

Mary Cowhey, a retired teacher in western Massachusetts, can personally attest to the lasting scars of hunger. She grew up on Long Island, in New York, part of a family of 10 that included six siblings and two cousins. Her father's salary as a teacher was insufficient to provide all the food they needed.

Every day after school Cowhey would help peel potatoes, their main source of nutrition. The family also survived on surplus shark, dropped off at their house by a local fisherman.

"And we were glad to have the shark and potatoes," she said, "because there were some times when we didn't [even] have the shark and potatoes."

Cowhey will never forget the pain of an empty belly, her envy of classmates' lunches and the competitive scramble when food hit the table.

"It was not uncommon for my sister to reach over and take something off my plate," she said. "So we learned to eat really fast."

Only the younger siblings got milk in her house. Cowhey still recalls the day of her first school physical, in fourth grade: "I remember the nurse letting me read the scale — you pushed the thing across — and it was 40 pounds."

She was 9 at the time; a healthy weight range for that age is 50 to 100 pounds, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Mary Cowhey experienced hunger as a child growing up on Long Island. In her adult life, she still feels the physical and psychological consequences of inadequate early nutrition. Karen Brown/NEPM hide caption

toggle caption

Karen Brown/NEPM

Cowhey became a single mom in her 20s. Unlike her parents, who were too embarrassed to seek help, she signed up for food stamps, the precursor to SNAP.

When Cowhey moved to Northampton, Mass., she would go to the local food pantry and tell her son to scooch forward in his stroller, so she could fit more food items behind him in the buggy.

"I was learning it was really important for kids to have milk and cheese and things like that," she said. "I didn't want him to ever grow up with that feeling of not having enough."

Cowhey is now 65 — thin, but no longer malnourished.

She graduated from college in her 30s and worked as a teacher and community organizer. She has also become an avid gardener, partly as a way to ensure she can grow some of her own food.

Nevertheless, after suffering a series of broken bones, Cowhey was diagnosed with severe osteoporosis — which she blames on a lack of calcium in childhood. Her bones are so brittle that her doctor says another fall could disable her, she said.

"It wasn't until I was in a back brace, flat on my back in a trauma center ... that I started to connect the dots," she said.

"I know that panicky feeling"

But the long-term effects of Cowhey's childhood hunger go beyond the physical. Although it has been decades since she lacked enough food, Cowhey still describes herself and her siblings as "opportunistic eaters."

"If there is food around, we will eat it. It has nothing to do with whether or not we're hungry. There's this mentality of 'in case there's not food tomorrow,'" she said. "For me, that never went away."

When President Trump briefly suspended the funding flow for food benefits during the government shutdown, Cowhey became upset and angry: "Because I know that panicky feeling."

Ramona Kallem, a volunteer, helps distribute food at the twice-a-week food bank outside the Easthampton Community Center.

Karen Brown/NEPM

hide caption

toggle caption

Karen Brown/NEPM

Conservative politicians point to fraud in the SNAP program as a reason to limit benefits and force states to turn over data on SNAP recipients. In late October, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins said SNAP has "just become so bloated, so broken, so dysfunctional, so corrupt that it is astonishing when you dig in."

But Chilton, the public health professor, says politicians are choosing to withhold SNAP benefits as a form of political maneuvering.

"They're forgetting that it actually has a real impact on people's everyday lives," Chilton said. "And I think they don't care. And that's because I think they haven't had enough exposure to the experience of hunger."

This story comes from NPR's health reporting partnership with New England Public Media and KFF Health News.

![Savory Vegan Granola [gluten-free + no added sugar]](https://i0.wp.com/healthyhelperkaila.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/SavoryGranola3.png?fit=800%2C800&ssl=1)

![Vegan Chinese 5-Spice Noodle Soup [gluten-free + oil-free]](https://i0.wp.com/healthyhelperkaila.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/ChineseNoodleSoup17.png?fit=800%2C800&ssl=1)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·